Georgians use the word “velvet” to describe the period when the summer heat has let up but autumn has not yet arrived, when nature is already preparing for winter but northerners can still derive pleasure and vitamin D by sunbathing. Velvet season lasts from late September to the second half of October, grapes are harvested and all of the market counters are full of agricultural produce. I think this is the best time to visit a people who have been living between the Caucasian mountain ranges for millennia.

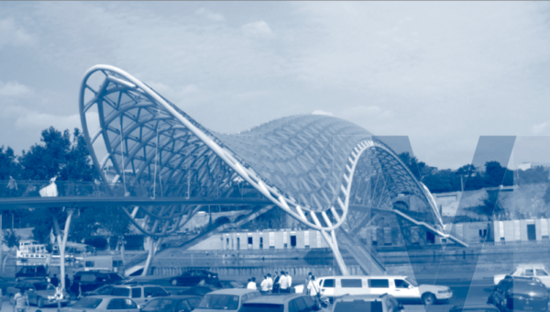

The capital, Tbilisi, has many good hotels but the well-informed traveller will find a selection of pleasant guesthouses, homes converted to B&B type affairs. We partook of the Georgelanders’ hospitality at a four-storey home stay called Babilina, featuring exciting, spontaneous architecture in the heart of the old town, near the Patriarchs’ Garden. Tbilisi’s city centre has everything experienced and more demanding tourists might crave – the old town’s warren of picturesque streets rendered exciting for the pedestrian by the topography, the main street, Rustaveli Avenue, with its wide sidewalks and whimsical street sculptures, the downtown area with its plentiful street cafés and wine bars, the glass pedestrian bridge over the River Kura (Mtkvari) – the Peace Bridge – and busy riverside thoroughfares. In the evenings, the city is illuminated, often luxuriantly so, with each tower and façade of any note lit by coloured beams of light. The city lies along a long valley between the mountains, following the curves of the river, and in the evening lights it is an entrancing sight.

Peace Bridge in Tbilisi. Photo: private collection.

Georgeophiles will quickly realize that this country and people have a very long history, their cultural stratum is inconceivably dense and closely connected with classical Asia Minor of antiquity and ancient Greece. The oldest churches were built in the 4th and 5th century CE, as Georgeland is one of the oldest Christian countries in the world. The people remain devoutly Orthodox today and churches are never empty in this land. The sacral architecture is different from that of the neighbouring peoples, the tapering church towers seem European, some spires are Gothically slender. An untrained eye cannot of course distinguish how the church interiors, iconography and liturgy differ from other Orthodox traditions, but it is clear that the architecture and symbolism are unusual and unique to Georgeland.

Gori is just 80 kilometres away from Tbilisi along the fourlane Batumi road. The historical Shida Khartli region, the Georgian heartland, has been blatantly rent apart, as Tskhinvali, the centre of the Russian-occupied region, is just 30 kilometres to the north. Even though Ossetians have sporadically settled here only in the last century, the region was dubbed South Ossetia on some bizarre whim by Gori native Jossif Dzhugashvili, known to the world as Stalin. That was as much pretext as Russia needed to overrun the southern side the Greater Caucasus and, along with occupying Abkhazia, put Georgia in a constant state of alert. Whole villages of big block houses – which can be seen lining the Gori-Tbilisi road – have been built for the 300,000 refugees displaced from the occupied areas. In spite of its extremely limited resources, the state is aiding its compatriots, but this contingent of inhabitants will remain a social problem for many years to come. At the same time, the areas now under the control of the large northern neighbour are devoid of people and to a large extent unused. We recognize the same signature despoliation in the Seto region of Estonia and on the other side of the River Narva, to say nothing of Karelia, formerly controlled by Finland.

A few dozen kilometres to the south of Gori is the cave town of Uplistsikhe, which is on the UNESCO World Heritage list. In its heyday, this amazing site, the beginnings of which date more than 3,000 years ago, was home to more than 20,000 people and an important link on the Silk Road between the Byzantine Empire and China. Only about a thousand lived in the caves proper, primarily patricians; the rest of the people lived in outlying settlements on the hillsides. Living quarters as well as temples, wine pressing facilities and artisans’ spaces were hewn into the stone – even a small theatre and seating. Although the city was abandoned 500 years ago, we can still see the beauty of the cave architecture right down to the intricate details of the ornaments, which have withstood countless earthquakes and even the bonfires lit by generations of shepherds for whom these were luxurious place of repose. A local guide, educated as an agronomist, and named Stalber (a common name around Gori), tells us that it was right here, in the southern part of Shida Khartli, that people first began to grow grapes, 9,000 years ago. Today’s grape cultivars mostly date back to this part of Georgeland, says the guide. In the 9th century, when Uplistsikhe still was thriving, a basilica was erected on the mountain that rises over the town. Today it and the cave town have been restored and made it readily viewable by culturally inclined tourists.

The historical Mtskheta-Mtianeti region lies north of Tbilisi. Part of this region, too – like Shida Khartli – is occupied by Russia. Along with the capital, Georgeland has 12 regions. Russia has lopped off pieces of four of these, swallowing the fifth region – Abkhazia – entire. President Mihheil Saakashvili was fortunate in able to bring a sixth region – Adzharia – back under central government control. Due to foreign aggression, Georgians have to secure and rebuild their country in a situation where hundreds of thousands of people were left homeless, historical routes were cut off and normal relations between different parts of the country were disrupted.

Mtskheta-Mtianetia is the southern terminus of the famous Georgian Military Road over the Greater Caucasus. The first half of this historical route leads north from Tbilisi along the valley of the River Aragvi until the great Jinvali reservoir, from there on along the Tetri Aragvi valley to the Jvuri gorge. From that point on, the military road follows the River Tereki valley. As the Russian occupation has closed other key routes over the High Caucasus (such as the Roki tunnel), this road, which ends in Vladikavkaz, Russia, has become an important transit channel for Armenian and Azerbaijan truckers. Up to the modern, luxurious Gudauri ski resort, the highway is in good condition and perfectly safe in spite of the mountainous terrain. From there on, to the Jvuri Pass at an elevation of 2,379 metres and down to Kobi village, the military road can only be negotiated safely by tanks. As Georgian vehicles cannot pass beyond the border checkpoint to Russia, Tbilisi is not interested in the costly maintenance of the road. This is what the locals say.

The road to the Jvuri Pass is an arduous journey in an ordinary Mercedes microbus, but the Caucasian truckers appeared to be quite self-confident in driving this road with its potholes and risk of falling rock. No doubt they have experienced worse! Along the way, tourists can marvel at the stunning Caucasian peaks and a grotesque mosaic installation which has adorned a flatter roadside area since 1983. This work, dedicated to the eternal friendship of the Russian and Georgian peoples and the bicentennial of the voluntary union of Georgia and Russia, marks the agreement signed between King Erekle II and Russia’s Catherine II to consign the Kakheti and Khartli areas to a Russian protectorate. Especially ghastly-looking on the backdrop of the history of the last decades is the depiction of the Russian soldier as victor.

The difficult trip is worth it, as a proper road begins again immediately north of Jvari. The banks of the upper Tereki are lined with villages. The high mountainsides and Alpine meadows with flocks of sheep offer picturesque views. The biggest and most important town in these parts is Stephantsminda, formerly known as Kazbegi – tidy and European, a regional centre bolstered by tourism whose best days were back when holidaymakers from Vladikavkaz and others from Russia came here. Northwest of Stephantsminda is famous Mount Kazbek, rising to 5.047 metres above sea level. Between clouds only glimpses of the high volcanic cone can be seen, but still, the views are high-mountain scenery at its best. The famous Holy Trinity Church of Gergeti can be seen clearly on the crest of a lower mountain. This is a favourite destination of many hikers. We did not undertake the three-hour hike due to time constraints, and used the services of some drivers of 4WD who took us up extremely exciting switchbacks of dirt road in half an hour.

Built in the 14th century the Gergeti Church is certainly not among the oldest in Georgia, but thanks to its location, with the high mountainsides of the High Caucasus directly behind it, it is one of the most iconic. The people of Stephantsminda frequent this church on every holiday, showing the outstanding physical condition, for the route is not an easy one and few drive 4WD vehicles. Fairly typically in these parts, monks live at the church, with their household affairs arranged around the church on the narrow mountain ridge.

Touring Georgia, one realizes why a woman in the closing scenes of Tengiz Abuladze’s film Repentance says that there is no point to roads that do not lead to a place of worship. The third tour our party undertook – eastward from Tbilisi, to Kakheti – also took us to a number of shrines and sanctuaries. The southern part of this county is a high steppe enlivened only by the sheep-farming city Udabno, where all buildings not in use by people – including half-finished structures – have been converted to hay barns. The south-eastern border of Georgeland runs along a relatively low, weathered mountain range where monks from Assyria back in the 6th century hewed out monastery rooms that have played a very important role in the country’s history over the centuries. In the 12th century Georgian King Demetrius I moved here after abdicating the throne. He was the author of the religious hymn “Shen Khar Venakhi” (“You Are a Vineyard”), an ode to divine viticulture.

The monastery was closed during the Soviet era and the Red Army base set up here trained soldiers for deployment to Afghanistan. In 1988 massive student demonstrations forced the Red Army to pull out and today the monastery is completely restored and full of life.

Kakheti is one of the most acclaimed wine-making regions in Georgia, with the vintages of the Telavi valley especially renowned. During the velvet season, the roadsides are full of sellers of local produce and most of them will offer travellers very good local Saperavi wine and chacha (homemade spirits). This bounty is offered generously to everyone interested in trying it. An inexperienced traveller has to be careful, as a few draughts can easily jeopardize the rest of the excursion! And certainly a goodly amount of fruit and wine can be procured from the roadside farm women – most of the sellers are sun-bronzed peasant women clad in folk costume – to enjoy them later in good company. The prices are reasonable, but everyone should be sure to try haggling skills, always a good way to communicate with people in the south.

Gori is just 80 kilometres away from Tbilisi along the fourlane Batumi road. The historical Shida Khartli region, the Georgian heartland, has been blatantly rent apart, as Tskhinvali, the centre of the Russian-occupied region, is just 30 kilometres to the north. Even though Ossetians have sporadically settled here only in the last century, the region was dubbed South Ossetia on some bizarre whim by Gori native Jossif Dzhugashvili, known to the world as Stalin. That was as much pretext as Russia needed to overrun the southern side the Greater Caucasus and, along with occupying Abkhazia, put Georgia in a constant state of alert. Whole villages of big block houses – which can be seen lining the Gori-Tbilisi road – have been built for the 300,000 refugees displaced from the occupied areas. In spite of its extremely limited resources, the state is aiding its compatriots, but this contingent of inhabitants will remain a social problem for many years to come. At the same time, the areas now under the control of the large northern neighbour are devoid of people and to a large extent unused. We recognize the same signature despoliation in the Seto region of Estonia and on the other side of the River Narva, to say nothing of Karelia, formerly controlled by Finland.

A few dozen kilometres to the south of Gori is the cave town of Uplistsikhe, which is on the UNESCO World Heritage list. In its heyday, this amazing site, the beginnings of which date more than 3,000 years ago, was home to more than 20,000 people and an important link on the Silk Road between the Byzantine Empire and China. Only about a thousand lived in the caves proper, primarily patricians; the rest of the people lived in outlying settlements on the hillsides. Living quarters as well as temples, wine pressing facilities and artisans’ spaces were hewn into the stone – even a small theatre and seating. Although the city was abandoned 500 years ago, we can still see the beauty of the cave architecture right down to the intricate details of the ornaments, which have withstood countless earthquakes and even the bonfires lit by generations of shepherds for whom these were luxurious place of repose. A local guide, educated as an agronomist, and named Stalber (a common name around Gori), tells us that it was right here, in the southern part of Shida Khartli, that people first began to grow grapes, 9,000 years ago. Today’s grape cultivars mostly date back to this part of Georgeland, says the guide. In the 9th century, when Uplistsikhe still was thriving, a basilica was erected on the mountain that rises over the town. Today it and the cave town have been restored and made it readily viewable by culturally inclined tourists.

The historical Mtskheta-Mtianeti region lies north of Tbilisi. Part of this region, too – like Shida Khartli – is occupied by Russia. Along with the capital, Georgeland has 12 regions. Russia has lopped off pieces of four of these, swallowing the fifth region – Abkhazia – entire. President Mihheil Saakashvili was fortunate in able to bring a sixth region – Adzharia – back under central government control. Due to foreign aggression, Georgians have to secure and rebuild their country in a situation where hundreds of thousands of people were left homeless, historical routes were cut off and normal relations between different parts of the country were disrupted.

Mtskheta-Mtianetia is the southern terminus of the famous Georgian Military Road over the Greater Caucasus. The first half of this historical route leads north from Tbilisi along the valley of the River Aragvi until the great Jinvali reservoir, from there on along the Tetri Aragvi valley to the Jvuri gorge. From that point on, the military road follows the River Tereki valley. As the Russian occupation has closed other key routes over the High Caucasus (such as the Roki tunnel), this road, which ends in Vladikavkaz, Russia, has become an important transit channel for Armenian and Azerbaijan truckers. Up to the modern, luxurious Gudauri ski resort, the highway is in good condition and perfectly safe in spite of the mountainous terrain. From there on, to the Jvuri Pass at an elevation of 2,379 metres and down to Kobi village, the military road can only be negotiated safely by tanks. As Georgian vehicles cannot pass beyond the border checkpoint to Russia, Tbilisi is not interested in the costly maintenance of the road. This is what the locals say.

The road to the Jvuri Pass is an arduous journey in an ordinary Mercedes microbus, but the Caucasian truckers appeared to be quite self-confident in driving this road with its potholes and risk of falling rock. No doubt they have experienced worse! Along the way, tourists can marvel at the stunning Caucasian peaks and a grotesque mosaic installation which has adorned a flatter roadside area since 1983. This work, dedicated to the eternal friendship of the Russian and Georgian peoples and the bicentennial of the voluntary union of Georgia and Russia, marks the agreement signed between King Erekle II and Russia’s Catherine II to consign the Kakheti and Khartli areas to a Russian protectorate. Especially ghastly-looking on the backdrop of the history of the last decades is the depiction of the Russian soldier as victor.

The difficult trip is worth it, as a proper road begins again immediately north of Jvari. The banks of the upper Tereki are lined with villages. The high mountainsides and Alpine meadows with flocks of sheep offer picturesque views. The biggest and most important town in these parts is Stephantsminda, formerly known as Kazbegi – tidy and European, a regional centre bolstered by tourism whose best days were back when holidaymakers from Vladikavkaz and others from Russia came here. Northwest of Stephantsminda is famous Mount Kazbek, rising to 5.047 metres above sea level. Between clouds only glimpses of the high volcanic cone can be seen, but still, the views are high-mountain scenery at its best. The famous Holy Trinity Church of Gergeti can be seen clearly on the crest of a lower mountain. This is a favourite destination of many hikers. We did not undertake the three-hour hike due to time constraints, and used the services of some drivers of 4WD who took us up extremely exciting switchbacks of dirt road in half an hour.

Built in the 14th century the Gergeti Church is certainly not among the oldest in Georgia, but thanks to its location, with the high mountainsides of the High Caucasus directly behind it, it is one of the most iconic. The people of Stephantsminda frequent this church on every holiday, showing the outstanding physical condition, for the route is not an easy one and few drive 4WD vehicles. Fairly typically in these parts, monks live at the church, with their household affairs arranged around the church on the narrow mountain ridge.

Touring Georgia, one realizes why a woman in the closing scenes of Tengiz Abuladze’s film Repentance says that there is no point to roads that do not lead to a place of worship. The third tour our party undertook – eastward from Tbilisi, to Kakheti – also took us to a number of shrines and sanctuaries. The southern part of this county is a high steppe enlivened only by the sheep-farming city Udabno, where all buildings not in use by people – including half-finished structures – have been converted to hay barns. The south-eastern border of Georgeland runs along a relatively low, weathered mountain range where monks from Assyria back in the 6th century hewed out monastery rooms that have played a very important role in the country’s history over the centuries. In the 12th century Georgian King Demetrius I moved here after abdicating the throne. He was the author of the religious hymn “Shen Khar Venakhi” (“You Are a Vineyard”), an ode to divine viticulture.

The monastery was closed during the Soviet era and the Red Army base set up here trained soldiers for deployment to Afghanistan. In 1988 massive student demonstrations forced the Red Army to pull out and today the monastery is completely restored and full of life.

Kakheti is one of the most acclaimed wine-making regions in Georgia, with the vintages of the Telavi valley especially renowned. During the velvet season, the roadsides are full of sellers of local produce and most of them will offer travellers very good local Saperavi wine and chacha (homemade spirits). This bounty is offered generously to everyone interested in trying it. An inexperienced traveller has to be careful, as a few draughts can easily jeopardize the rest of the excursion! And certainly a goodly amount of fruit and wine can be procured from the roadside farm women – most of the sellers are sun-bronzed peasant women clad in folk costume – to enjoy them later in good company. The prices are reasonable, but everyone should be sure to try haggling skills, always a good way to communicate with people in the south.

The Bibilon pension. Photo: private collection

Sighnaghi is an attractive regional centre in Kakheti, which has been developed into a tourist trap. Everything is as it should be in a typical European mountain town, with winding cobblestone streets and a towering town hall spire. The city with its souvenir shops and cafes may be too sterile for thrill-seeking tourists, but Georgeland undoubtedly needs romantic spots like these, too, to become a destination for bus package tourists. A few kilometres to the south is the lavish Bodhe convent, site of the St. Nino nunnery. It offers good views of the mountain horizon, walks in the quiet convent park and a resplendent array of memorabilia from the gift shop.

To truly get to know Georgeland, one must spend a number of velvety weeks there. A week might be enough to get a sense of the country’s cultural wealth, but the country has enough to offer to fill entire years. Even today, Georgeland is full of positive surprises, as a new era is dawning far from the city centre of Tbilisi. The government plans to consolidate all services in the Justice Ministry’s area of administration at a network of service outlets so that people can tend to all of their business with the state in a short time – from birth certificates and marriage licenses to establishing companies. In Rustavi, a city of about 100,000 ten or so kilometres southeast of Tbilisi, we see the first such service outlet, of which 22 are planned countrywide. The stateprovided service is likely more progressive than in most countries in continental Europe.

Like Estonia, Georgeland must be an overachiever and forward-looking to ensure a secure future for its people. The people seem to be aware of this, and there are clear signs that this inseparably European country’s rich history could one day be complemented by becoming an exemplary part of the European Union.

To truly get to know Georgeland, one must spend a number of velvety weeks there. A week might be enough to get a sense of the country’s cultural wealth, but the country has enough to offer to fill entire years. Even today, Georgeland is full of positive surprises, as a new era is dawning far from the city centre of Tbilisi. The government plans to consolidate all services in the Justice Ministry’s area of administration at a network of service outlets so that people can tend to all of their business with the state in a short time – from birth certificates and marriage licenses to establishing companies. In Rustavi, a city of about 100,000 ten or so kilometres southeast of Tbilisi, we see the first such service outlet, of which 22 are planned countrywide. The stateprovided service is likely more progressive than in most countries in continental Europe.

Like Estonia, Georgeland must be an overachiever and forward-looking to ensure a secure future for its people. The people seem to be aware of this, and there are clear signs that this inseparably European country’s rich history could one day be complemented by becoming an exemplary part of the European Union.

The trip to Georgia took place from 23 September 2011 to 3 October accompanied by former and current staff members of the State Archive.