Knowing that the Ukrainian economy and defence forces have been reduced to chaos owing to the fights between its oligarchs and corruptive activities, Putin and Co. decided to start a game of poker. The prize is the state of Ukraine, the pro-Russian areas of which being absorbed into the Russian Federation, and the rest of Ukraine becoming Russia’s obedient vassal not as a member of the European Union or NATO, but of the Eurasian Union.

At the beginning of the poker game, Putin tried to use its arsenal of soft power, announcing through the country’s propaganda machinery that Ukraine had a vast gas debt to Russia, which could be partly compensated by acting in a manner that is to Russia’s liking. All this irritated the then Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych. Knowing that both the US (under the EU–US free trade agreement) and the People’s Republic of China (under the New Silk Route project) intended to use the Crimea in the future as a transhipment point for cheap goods to be supplied to Europe, Yanukovych began to intimate to the leaders of these countries that the one who pays a large sum of money into the pocket of the Yanukovych clan for a long-term lease agreement of the Crimea would immediately receive the signature of the Ukrainian leader on the contract.

We now know that Yanukovych’s financial request was too big for the two great powers and the Crimea was not rented out. However, the Russian intelligence services heard of Yanukovych’s pimping of the Crimea and realized it was the last moment for President Putin to speed up his poker game. The first thing he had to do was get back to Russia the Crimea along with Sevastopol, which was of interest to the great powers and where the Russian Black Sea Fleet was trapped under an expensive long-term lease. This action was facilitated by the fact that the Crimea was one of Ukraine’s poorest oblasts in socio-economic terms and there was much discontent with Kyiv’s central government.

Very conveniently for the Kremlin, the anti-Yanukovych unrest in Kyiv was activated by the US, which had a disagreement with Yanukovych, followed by several other countries in the West. The Maidan events began to have a considerable influence on Ukraine’s political affairs. The Kremlin’s leaders found that the time was ripe for a poker-style bluff. The Russian mass media began to sing a chorus to the effect that the Khrushchev’s Soviet-era gift of the Crimean peninsula and the city of Sevastopol to Ukraine was an illegal act and that the areas had to be returned to Russia. Almost at the same time, unrest began in the Crimea, where the Russian-speaking masses demanded that Crimea be annexed by Russia and a referendum organized on the issue. Although the local Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians were sharply opposed to such unrest, their voice was not heard. On the contrary, fully armed, unmarked sturdy ‘green men’ appeared in the Crimea, who suppressed any anti-Russian protests with force or sent the protesters out of the Crimean peninsula.

This allowed the Kremlin to announce that the referendum on the status of Crimea would be held on 16 March 2014. To the astonished international public, President Putin bluffed that the uniforms and equipment of the ‘green men’ must have been obtained from local kiosks and that Moscow was not connected with any of this. As expected, under the supervision of the green men with automatic guns, the Crimeans voted to join Russia, and the Crimean peninsula and the city of Sevastopol with all their immovable and movable property were smoothly transferred to the Russian authorities – without a single gunshot. The Kremlin led by Putin had achieved a great victory over Ukraine in the first round of the poker game.

Even many well-known opposition figures, such as Alexei Navalny and Boris Nemtsov, rejoiced over having the Crimea back as part of Russia. The former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, usually a bitter critic of the Kremlin’s actions, announced in the Russian mass media that the Crimea was an historical part of Russia, a ‘child of Russia’, which it was again lucky to be. Both the leaders and the people were overjoyed with the victory, the latter lifting Putin to unprecedented heights in their popularity ratings. This was a sign to the Kremlin that the high-stakes game in Ukraine should be continued.

The first task was to prepare for the takeover of the mainly Russian-speaking eastern Ukrainian oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk, which were also the location of military factories important for the Russian military industrial complex. The Russian agency placed in the area a year or a year and half earlier was ordered to groom the local inhabitants for separation from Kyiv, where the corrupted power of Yanukovych had been replaced by Western-minded authorities in the course of the Maidan events.

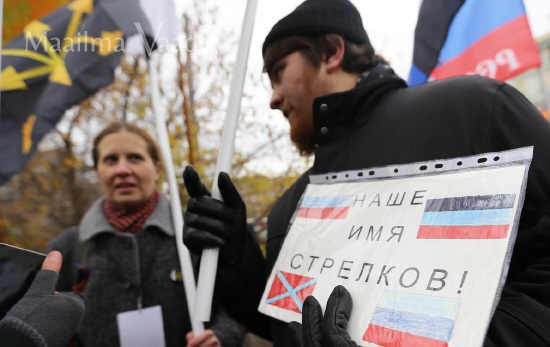

This showed to the Kremlin that the poker game in Ukraine was not going quite according to its plan. Alexander Borodai, member of the Moscow-based ruling party United Russia, was sent to be the prime minister of the ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’, which had already been declared according to Moscow’s scenario. Igor Girkin-Strelkov, senior officer of the GRU from Moscow, was appointed as the defence minister of the ‘People’s Republic’. While the former’s orders were immediately disobeyed by the local people who called Borodai a Moscow bureaucrat (at which, to Moscow’s great disappointment, he soon resigned from the post of the ‘prime minister’) Girkin-Strelkov at once got into a conflict with another GRU senior officer, Igor Bezler, who found that he as an older and more experienced candidate should really be the defence minister of the ‘People’s Republic’.

Later, Aleksandr Zakharchenko, who replaced Borodai as the prime minister, and Girkin-Strelkov were even involved in a brief shooting, in which the latter was wounded in a hand and a leg and was placed in the Rostov army hospital. Several other emissaries from Moscow were also disgraced by the locals. On the initiative of Girkin-Strelkov, they started to send complaints to Moscow and give accusatory interviews as if the Kremlin only supplied them with clothes, tinned food and medicines, but deliberately left them without weapons to protect against the attacks of the anti-terrorist units of the Ukrainian army.

This was a serious alarm signal to Putin. He consulted his henchmen, but got very mixed advice. His communist adviser Sergei Glazev advised to quickly force the Kyiv authorities to their knees by a massive bombing of Ukrainian cities. Several generals of the general staff advised a broad-scale invasion of Ukraine by the army. This idea was supported by many members of the elite clubs Izborski Klub and Krasnaya Moskva, which had influence on the Kremlin. In such a situation, President and Commander-in-Chief Putin felt squeezed. According to the information that seeped through the walls of the Kremlin, the head of state was so depressed that he didn’t even wish to celebrate his birthday in Moscow but spent the event in the silence of the Siberian taiga, accompanied by a few bodyguards.

Luckily, Putin was not able to send his army against Ukraine at the time, because according to Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu, three serious arguments spoke against it:

1) Russia had no wartime headquarters or ‘stavka’ or the necessary staff;

2) the Russian army did not have enough mobile ambulance units;

3) the local volunteers in the Donetsk and Luhansk ‘People’s Republics’ had not undergone sufficient military training by the Russian GRU men and military instructors.

An invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army would thus have been a great military adventure that could have given reason for international intervention and serious accusations of Russia. However, the Russian military leadership found that it was worth to repeat the experience of the Russian–Georgian military conflict of 2008, in which ‘humanitarian aid’ convoys were dispatched to Abkhazia and South Ossetia, most of them containing weapons for the rebels against the Georgian authorities rather than clothes, food or medicines.

In midsummer 2014, long white-painted convoys of Kamaz trucks started to move toward the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, which had been occupied by separatists. It soon turned out that some of the trucks arrived at their destination empty or filled with mysterious sealed boxes, and representatives of the Red Cross were not invited to inspect their contents. This coincided with raids of the military factories in these oblasts, where the expensive fixtures were dismounted, loaded on the same white-painted humanitarian Kamaz trucks and transported to Russia. The Kremlin’s hope to manufacture in Russia the military products that it would otherwise not receive from Ukraine will probably not materialise, as most of the technical and technological documentation of the machinery is kept in Kyiv. The equipment that was robbed from the Ukrainian military industry can therefore be used in Russia only as scrap metal or for the manufacture of certain peacetime products.

Seeing the little effect of these actions, the Kremlin is now being hypocritical and clearly bluffing to the international public. Tanks, armoured transporters, mobile cannon, air defence devices and other heavy military equipment are being sent across the Russian–Ukrainian border to the separatist oblasts in broad daylight. Any Russian spies or staff officers captured by the Ukrainian forces are instantly titled by the Russian media and the official Moscow as ‘volunteers on holiday’ or ‘persons who unintentionally crossed the separatist border’.

The international public ceased to believe these stories long ago. According to Dmytro Tymchuk, head of the eastern Ukrainian underground organisation Information Resistance, the Kremlin dispatched about 110 tanks, 250 armoured transporters, 100 cannon and bazookas and 500 military vehicles to the separatists in October 2014. About 15,000 Russian mercenaries are now active on Ukrainian territory. They are supported by nearly 12,000 local separatist fighters. All these forces are divided between four ‘military activity areas’.

It is clear that the Kremlin can no longer deny a military force of such capacity or call it something given to the eastern Ukrainian separatists as a minor mistake. The stories by the Kremlin bosses about the volunteer Russian fighters on holiday in eastern Ukraine is also peculiar. Section 395 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation clearly states that the dispatch of Russian citizens as mercenaries to foreign countries is prohibited and qualifies as a crime. Unfortunately, Putin and his cronies have decided to close their eyes to these activities in Ukraine. Quite the opposite is actually evident. For example, the notorious Igor Bezler, commander of the Gorlivka garrison, was lately ceremonially retired by the heads of the Donetsk ‘People’s Republic’ by awarding him the rank of a major general and a classy apartment in the Crimea. The equally notorious Girkin-Strelkov was given a desirable job as a host on national television (the successful writer of fairy tales in his youth is now leading a popular children’s series) and a nice place to live in Moscow.

Compassion is due to the latest leaders of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, who have tried to leave their unpromising jobs but are prohibited by Moscow to do so. The desperate leaders of Donetsk organised their own ‘parliament elections’ guarded by armed units, which nobody but Russia recognizes as democratic. However, the chairman of the central commission of these elections Roman Lyagin told journalists that according to the election results, Donbass had finally separated from Ukraine. The seriousness of his decision is confirmed by the supreme council of the Donetsk ‘People’s Republic’, which has decided to soon start printing its own money to replace the Russian roubles and Ukrainian hryvnias currently in use.

It would be interesting to know where the money would be printed, because the leaders of Belarus have officially denounced the eastern Ukrainian separatism. The Russian leader Putin only lately repeated that it wished to see Ukraine as a territorially intact federal state and did not support separatism in this context. It is also clear to Russia that its active support of separatism in eastern Ukraine has led the West to impose strict sanctions on Russia, the bitter effects of which Russia is already tasting.

|

The cutting off of Western credit sources has suddenly placed Putin’s old Chekist friends, who are leaders of state-owned companies, and their huge businesses in a dire economic situation. In order to escape the situation, executive chairman of Rosneft Igor Sechin, CEO of Rostech Sergey Chemezov, and president of the Russian Railways Vladimir Yakunin are now asking the government to pay subsidies amounting to one and half trillion or more roubles. As the state’s currency reserves have shrunk to a level of approximately 420 billion dollars, of which state-owned companies can only apply for a part of a sum of about 210 billion dollars, it is understandable that neither the finance ministry nor Putin can meet these requests of trillions of roubles.

All this has put tension on the relations of the oligarchs with the Kremlin and government and also between themselves. The import embargos that were imposed as a countermeasure to the sanctions against Russia have pushed the prices of food and consumer goods up to a high level. In September, Putin was still hoping the annual inflation would remain under 8%, but considering the current economic situation, Economic Development Minister Alexey Ulyukaev finds that 9% would be a good result. The former Finance Minister Aleksei Kudrin believes, not without reason, that Russia may lose 15% of its gold reserves to the Western sanctions.

The oil prices on the world market are no consolation to the Kremlin either. Although the finance ministry prepared the federal budget expecting the world market price for a barrel of oil not to fall below 96 dollars, it has already dropped to below 60 dollars. One of Russia’s main sources of income, oil, is thus becoming a secondary source. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov tries to keep up a good face and says that economic crisis can only happen if the price of a barrel falls below 60 dollars. But even some of his colleagues in the government advise not to take this seriously. This is also why Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev demanded a quick review of the federal budget in mid-November.

At the same time, the constantly depreciating rouble is causing growing fear in Russian business circles. The central bank’s summer statement that it had sufficient reserves to stabilise the exchange rate of the rouble is no longer valid. Even President Putin now demands that the rouble’s exchange rate be allowed to float freely. Figuratively speaking, Putin is beginning to agree with a situation in which he lacks resources to continue a powerful poker game in the Ukraine, while he also lacks the political courage to admit it.

As a political gambler who is afraid to take responsibility in the Ukrainian affair and lose his momentary peak popularity, Vladimir Putin has decided, according to his words, to distance himself from it. As lately as on 18 November, on his meeting with the German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Putin complained that he wished the bloodshed in eastern Ukraine to end and the conflict to be regulated in the spirit of Minsk agreements. But as Russia, in Putin’s words, did not participate in the conflict, only negotiations between the Kyiv authorities and the ‘People’s Republics’ can succeed in accomplishing this task.

So this was another poker bluff, claiming that the Kremlin had not supplied the eastern Ukrainian separatists/terrorists with military specialists or equipment. No thinking person believes these statements by Putin any more. The Kremlin should admit that as the conflict and sanctions continue, time will only lead the country to economic collapse.

All this has put tension on the relations of the oligarchs with the Kremlin and government and also between themselves. The import embargos that were imposed as a countermeasure to the sanctions against Russia have pushed the prices of food and consumer goods up to a high level. In September, Putin was still hoping the annual inflation would remain under 8%, but considering the current economic situation, Economic Development Minister Alexey Ulyukaev finds that 9% would be a good result. The former Finance Minister Aleksei Kudrin believes, not without reason, that Russia may lose 15% of its gold reserves to the Western sanctions.

The oil prices on the world market are no consolation to the Kremlin either. Although the finance ministry prepared the federal budget expecting the world market price for a barrel of oil not to fall below 96 dollars, it has already dropped to below 60 dollars. One of Russia’s main sources of income, oil, is thus becoming a secondary source. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov tries to keep up a good face and says that economic crisis can only happen if the price of a barrel falls below 60 dollars. But even some of his colleagues in the government advise not to take this seriously. This is also why Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev demanded a quick review of the federal budget in mid-November.

At the same time, the constantly depreciating rouble is causing growing fear in Russian business circles. The central bank’s summer statement that it had sufficient reserves to stabilise the exchange rate of the rouble is no longer valid. Even President Putin now demands that the rouble’s exchange rate be allowed to float freely. Figuratively speaking, Putin is beginning to agree with a situation in which he lacks resources to continue a powerful poker game in the Ukraine, while he also lacks the political courage to admit it.

As a political gambler who is afraid to take responsibility in the Ukrainian affair and lose his momentary peak popularity, Vladimir Putin has decided, according to his words, to distance himself from it. As lately as on 18 November, on his meeting with the German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Putin complained that he wished the bloodshed in eastern Ukraine to end and the conflict to be regulated in the spirit of Minsk agreements. But as Russia, in Putin’s words, did not participate in the conflict, only negotiations between the Kyiv authorities and the ‘People’s Republics’ can succeed in accomplishing this task.

So this was another poker bluff, claiming that the Kremlin had not supplied the eastern Ukrainian separatists/terrorists with military specialists or equipment. No thinking person believes these statements by Putin any more. The Kremlin should admit that as the conflict and sanctions continue, time will only lead the country to economic collapse.

|