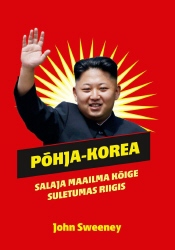

One would think that a country like the People’s Republic of North Korea could not exist in the 21st century, if it weren’t right there in front of us. The book was written by the well-known British investigative journalist and author John Sweeney, who as an Observer and BBC journalist has covered more than 60 countries, including such hotspots in war zones as Algeria, Iraq, Chechnya, Bosnia and Ceausescu’s Romania. The author’s extensive experience and ability to see reality behind the wall of illusion gives readers an unsettling but objective look at the most brutal tyranny on earth today. When it was first published, the book set off a proper scandal as Sweeney couldn’t gain access to North Korea as a journalist. He thus relied on the credentials of an academic from the London School of Economics, for which he was accused of exploiting the school and putting students at risk. But the book couldn’t have been written any other way.

One would think that a country like the People’s Republic of North Korea could not exist in the 21st century, if it weren’t right there in front of us. The book was written by the well-known British investigative journalist and author John Sweeney, who as an Observer and BBC journalist has covered more than 60 countries, including such hotspots in war zones as Algeria, Iraq, Chechnya, Bosnia and Ceausescu’s Romania. The author’s extensive experience and ability to see reality behind the wall of illusion gives readers an unsettling but objective look at the most brutal tyranny on earth today. When it was first published, the book set off a proper scandal as Sweeney couldn’t gain access to North Korea as a journalist. He thus relied on the credentials of an academic from the London School of Economics, for which he was accused of exploiting the school and putting students at risk. But the book couldn’t have been written any other way.Sweeney illustrates life in North Korea by providing numerous examples of the fate of specific people, using their cases to analyze the nature of the regime and looking for its roots in comparison to other totalitarian countries. He arrives at the slightly debatable conclusion that its ideology of racial purity puts North Korea closer to Nazi Germany than to other communist countries. But this comparison does have its merits if one considers that Nazi Germany and Stalin’s USSR were actually very similar regimes, and thus dictator Kim Il Sung’s version of Stalinism did indeed yield a hybrid of communism and national socialism.

Sweeney shows that North Korean society is hypocritical and duplicitous to an extreme. Based on socialist ideas,

which holds that equality of all is the supreme value, North Korea is probably the most unequal society in today’s world –a huge chasm gapes between the oligarchy and ordinary people and leaders are like demigods. Positions in the ruling class are passed on by right of birth, while ordinary people live on the verge of famine. Socialism’s goal of eliminating human exploitation has in North Korea’s case manifested, concentration camps with inhuman conditions, and the state has been yoked into the service of the unrestrained egotism of the ruling class. Ideals have ceased to exist for the leaders of this country, the people are kept in the dark, in a fearful climate of propaganda based on total lies, and secrecy. North Korea is the perfect example of how communist ideals and reality are mutually exclusive.

How long can such a slave labour camp continue to exist? When Kim Il Sung died, there were hopes that the regime would be forced to become more liberal. Yet only mass executions followed his death. Still, Sweeney is hopeful, saying that the tyranny won’t survive 50 years, as a Romanian diplomat fears it will in the book. But the end often comes unexpectedly for totalitarian countries. They can last decades; but tomorrow they’re gone. It is a painful and urgent question how people who have been brainwashed for generations can adapt to democracy and how much time it will take.

I recommend the book to everyone interested in Korean history, the peculiar logic that totalitarian operate by, and in particular, the reality of communism.