The friendship between the legal predecessor of the Russian Federation – the Soviet Union – and China began blossoming in the last few months of World War II, when Soviet leader Josef Stalin sent the Red Army to drive out the Japanese from Manchuria and other Chinese-settled areas. The increasingly warmer friendship and cooperation between the Soviets and China lasted until Nikita Khrushchov rose to power in the late 1950s. Continued warmer relations between the superpowers proved elusive during the Brezhnev and Yeltsin years, due to diverging opinions on the development of socialism and escalating territorial disagreements in border regions, which went as far as open hostilities over Chinese-occupied Damansky Island in the Amur River.

Outwardly, Sino-Russian relations began warming up quickly in the first few years of Vladimir Putin’s second term as president, from 2004. Although the Communist Party retained control in China, the country’s top leaders embarked on a course of radical market reforms where foreign investments also played an important role. Although Russia had been on a publicly declared path of capitalist development for years, its radical reforms often bogged down in bureaucracy and crime. In the new situation, rapidly growing Chinese industry needed more and more oil and gas from Russia while the latter craved cheap Chinese-made electronics and textiles.

From 2006 on, China’s gross domestic product grew at least 7-8 per cent per year; state revenue grew as well. This allowed the country’s leaders, driven by territorial ambitions, to increase military spending to a record 61.9 billion USD in 2008. Both US Pentagon reports to Congress and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute have stressed that China actually conceals part of its military spending and the declared amounts should be multiplied by a coefficient of at least 1.4. As China has not been immune to the negative effects of the global economic crisis, its military spending in recent years has hovered around the 2008 figure. Yet the Chinese military industry needs a serious technological upgrade, especially as pertains to shipbuilding and aircraft engineering. Neither the West nor Russia desires to equip China with modern military technology. However, Russia has agreed to sell China various jet fighters and diesel submarines as well as surface ships with other functions. Russia has also sold China a number of licenses to manufacture light weaponry (such as Kalashnikov automatic rifles).

This is not enough for the needs of the People’s Liberation Army, and thus China is busily engaged in industrial espionage, hoping to copy the modern weaponry used in other countries. They are also trying to exploit various foreign intermediaries and one-hand-feeds-the-other opportunities in foreign countries to evade the sale embargo established by industrialized countries on state-of-the-art weapons. For instance, in 2011 China attempted to procure 69 US-made Patriot antiaircraft missiles through Israel, even though the majority of modern AA missiles are embargoed in NATO states and Russia. The goods did not make it to China that time, as the ship carrying them, the Thor Liberty, was subjected to inspection in the Finnish port of Kotka, the actual final destination of the cargo was found out in spite of misleading covering documents that indicated the goods were bound for South Korea.

Yet China has made major forward strides in the field of missile systems. According to the news.rambler.ru/asia site, the Chinese corporation CPMIEC in spring 2011 handed over to the Chinese armed forces a new, modern, modular operational tactical complex with a radius of at least 400 kilometres. As this is a hybrid of two previous systems already in production in China – the SY-400 and BP-12A – located on a truck platform called WS-2400, this mobile complex can fire both 400 mm and 600 mm calibre rockets, with a payload of close to 300 kg and has a number of warhead options. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army is currently known to have over 150 mobile missile batteries and over 15,000 anti-aircraft artillery or zenithal heavy machine guns. China has a well-developed reactive artillery, with firing equipment operating in the calibre range of 273–320 mm. The firing power of the latter is fully comparable to the famous American MLRS and Russian Smerch systems.

At the urging of a personal close friend of President Putin from KGB days and the current president of Rosneft, Igor Sechin, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s 4th anti-aircraft has obtained modern Tor AA missiles of Russian origin. Chinese-made Type-96 tanks are also among the best in the world. But all these state of the art weapons are controlled by the Beijing and Shenyang military regions, the former being oriented to engaging Russia’s Siberian military district, the latter to counter Russia’s Far Eastern military forces.

Outwardly, Sino-Russian relations began warming up quickly in the first few years of Vladimir Putin’s second term as president, from 2004. Although the Communist Party retained control in China, the country’s top leaders embarked on a course of radical market reforms where foreign investments also played an important role. Although Russia had been on a publicly declared path of capitalist development for years, its radical reforms often bogged down in bureaucracy and crime. In the new situation, rapidly growing Chinese industry needed more and more oil and gas from Russia while the latter craved cheap Chinese-made electronics and textiles.

From 2006 on, China’s gross domestic product grew at least 7-8 per cent per year; state revenue grew as well. This allowed the country’s leaders, driven by territorial ambitions, to increase military spending to a record 61.9 billion USD in 2008. Both US Pentagon reports to Congress and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute have stressed that China actually conceals part of its military spending and the declared amounts should be multiplied by a coefficient of at least 1.4. As China has not been immune to the negative effects of the global economic crisis, its military spending in recent years has hovered around the 2008 figure. Yet the Chinese military industry needs a serious technological upgrade, especially as pertains to shipbuilding and aircraft engineering. Neither the West nor Russia desires to equip China with modern military technology. However, Russia has agreed to sell China various jet fighters and diesel submarines as well as surface ships with other functions. Russia has also sold China a number of licenses to manufacture light weaponry (such as Kalashnikov automatic rifles).

This is not enough for the needs of the People’s Liberation Army, and thus China is busily engaged in industrial espionage, hoping to copy the modern weaponry used in other countries. They are also trying to exploit various foreign intermediaries and one-hand-feeds-the-other opportunities in foreign countries to evade the sale embargo established by industrialized countries on state-of-the-art weapons. For instance, in 2011 China attempted to procure 69 US-made Patriot antiaircraft missiles through Israel, even though the majority of modern AA missiles are embargoed in NATO states and Russia. The goods did not make it to China that time, as the ship carrying them, the Thor Liberty, was subjected to inspection in the Finnish port of Kotka, the actual final destination of the cargo was found out in spite of misleading covering documents that indicated the goods were bound for South Korea.

Yet China has made major forward strides in the field of missile systems. According to the news.rambler.ru/asia site, the Chinese corporation CPMIEC in spring 2011 handed over to the Chinese armed forces a new, modern, modular operational tactical complex with a radius of at least 400 kilometres. As this is a hybrid of two previous systems already in production in China – the SY-400 and BP-12A – located on a truck platform called WS-2400, this mobile complex can fire both 400 mm and 600 mm calibre rockets, with a payload of close to 300 kg and has a number of warhead options. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army is currently known to have over 150 mobile missile batteries and over 15,000 anti-aircraft artillery or zenithal heavy machine guns. China has a well-developed reactive artillery, with firing equipment operating in the calibre range of 273–320 mm. The firing power of the latter is fully comparable to the famous American MLRS and Russian Smerch systems.

At the urging of a personal close friend of President Putin from KGB days and the current president of Rosneft, Igor Sechin, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s 4th anti-aircraft has obtained modern Tor AA missiles of Russian origin. Chinese-made Type-96 tanks are also among the best in the world. But all these state of the art weapons are controlled by the Beijing and Shenyang military regions, the former being oriented to engaging Russia’s Siberian military district, the latter to counter Russia’s Far Eastern military forces.

Chinese workers prepare a road for paving in the Irkeshtam Pass, a border crossing with China, in Kyrgyzstan, on Sept. 7, 2010. While China is seizing the spotlight in East and Southeast Asia with its widening economic footprint and muscular diplomacy, it is also quietly making its presence felt on its western flank, once primarily Russians domain. Photo: Scanpix

Chinese leaders have put special focus on their 38th Army, which is located in the immediate proximity of the border with Russia’s Primorye Krai. China’s leaders make no secret about the fact that this is an offensive force. It incorporates the 6th tank division with ultramodern weaponry, and powerful artillery divisions with guns mounted on platforms equipped with automatic loading and precision computerized targeting systems, which are trained to cover 1000 km of ground per day in Siberia. Meanwhile, the Chengdu and Guangzhou district forces, oriented to India and Indonesia, have relatively modest means and out-dated types of weaponry.

This is a telling example of the “friendly sentiment” that China harbours toward Russia compared to its other neighbours. Already in 2004 and 2005, the sensationalist-leaning Russian newspapers Zavtra and Versiya trumpeted the fact that the People’s Republic had part of its strategic missiles trained on Russia’s largest cities. In September 2006, Russia’s major dailies described the major joint manoeuvres conducted over a period of 10 days by the Beijing and Shenyang military regions, which simulated an invasion by these forces into Siberia along with different types of battles. One of Russia’s leading military experts Aleksandr Khramtshikhin noted that the main goal of the exercises was to prepare for an offensive war against the Russian Federation. The presidential Kremlin and Russian cabinet remained silent.

China’s military preparations against Russia were not discussed at the October 2008 meeting between Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao and Vladimir Putin. Instead, the two countries’ well-organized bilateral joint military exercises were praised, these having been conducted in the interim on Russian Federation territory; and agreements were signed for the construction of a gas pipeline from Russia to China and on oil delivery worth 25 billion USD. Resenting the EU’s criticism of Russia over the Georgia-Russia military conflict, the Russian state media announced on 27 October that Russia had decided pursuant to a government decision to re-orient exports from the European Union to China, and, to some extent, to India. The results of this decision were apparent in 2011, when trade between Russia and China increased to a record 83.5 billion USD. Yet as the world’s leading business newspapers reported, the volume was still 4.5 times less than Russian-EU trade, thus a major shift did not actually take place. However, the topics at a meeting of Chinese leaders on 6 December 2011 leaked out to Russian leaders and later, the public. At that meeting, President Hu Jintao spoke, urging his naval forces to prepare for combat. He intimated in fairly direct language that China would face a natural resource and territory crunch in years to come and it would have to be ready for military conflict with neighbouring countries with which China has disputed territories: Brunei, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and possibly a larger country.

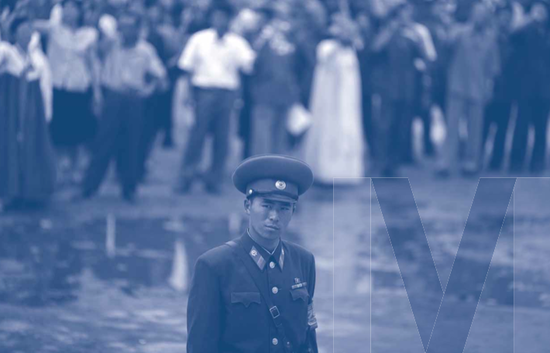

A soldier stands guard as local residents attend the departure ceremony of the Mangyongbyong cruise ship in the port area of North Korean Special Economic Zone of Rason City, northeast of Pyongyang August 30, 2011. North Korea launched itself into the glitzy world of cruise tourism when about 130 passengers set sail from the rundown port of Rajin, near the China-Russia border, for the scenic Mount Kumgang resort near the South Korean border. Isolated North Korea s state tourism bureau has teamed up with a Chinese travel company to run the country s first ever cruise aboard an ageing 9,700 tonne vessel which once plied the waters off the east coast of the divided peninsula shuttling passengers between North Korea and Japan. Picture taken August 30, 2011. Photo: Scanpix

Rumours started spreading in Russia’s corridors of power. Putin’s entourage, anxious over the reports, saw fit to believe that the unnamed large country was the US, which considering Russia’s strategic interests would not be bad at all as an option. But already in May 2012, Chinese Defence Minister Lian Guanle visited the US. During his visit, the Chinese government mouthpiece Renmin Ribao wrote that developing Chinese-American economic and trade relations would allow the still-existing deficit of trust to be overcome and avoid a military stand-off in the Asian Pacific. This assessment was like a cold shower for the Kremlin, which had staked its bets on worsening Sino-American relations, especially in light of the joint Chinese-Russian naval exercise held in April, “Morskoye vzaimodeistviye 2012” in the Yellow Sea near Qingdao. The Kremlin hoped those exercises would inspire greater respect from China. But although Russia brought out all of its top vessels, such as the missile carrier Varyag and the destroyers Admiral Tributs and Marssal Shaposhnikov, the journalists covering the exercise reported that they were outclassed by the ultramodern aircraft carrier shown off by China.

Regarding these exercises, deputy director of the Political and Military Analysis Institute Aleksandr Khramchikhin wrote in leading Russian newspapers that the “Chinese used the Russians at the joint naval exercises only to show their compelling superiority.” In China’s leading papers, the well-known Chinese military expert Fan Bin emphasized that for China, building and utilizing an aircraft carrier was an inevitable step for demonstrating its military edge. Now even less prominent Russian mass media channels started recalling warnings from the country’s leading Sinologists (e.g. Alexander Sharavin and Andrei Piontkovsky) from 2010 that China was continually increasing its military presence along Russian borders, which could lead to a military conflict. They also recalled Piontkovsky’s opinion that the fate of Russia’s Far Eastern region would be to serve China’s energy and raw material needs, and that this would be accompanied by the massive influx of Chinese into Siberia.

Putin and his advisers dismissed such warnings. They (and in particular, Sergei Prikhodko) countered that only 6.7 million people inhabit Russia’s Far East, of whom Chinese make up a negligible share and that Sinification was not taking place. And Putin has also bestowed high praise on ten “decisive” (Putin’s expression) agreements signed on a visit to China in connection with the 12th session of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which would transform the “good friendship” between China and Russia in the field of atomic energy, oil and gas, tourism, high tech and helicopter research into a “good partnership of a world calibre”.

The world s oldest known carpet from a Pazyryk mound on display at the Hermitage Museum. Entitled Ancient Siberia: 5th Pazyryk Mound, the exhibition features burial artefacts of the 5-3rd century BC from the ancient mound in the Altai Mountains on the Russians western borderline to China. Photo: Scanpix

As seemingly an ironic riposte to this assessment, word came from China on 14 August 2012 tat China was seeking, in border negotiations in the Altai, a 17-hectare area from Russia. As to China’s desire to engage in joint helicopter development projects, Russia’s leading military experts have long spoken of the risks of this cooperation, noting that China still lacks attack helicopters today and that the conventional ones they have are constantly prone to accidents. Their logic: why furnish China with better machines if they could be turned against Russia someday? And with regard to Putin’s vaunted cooperation with China in the framework of Shanghai Cooperation Organization, according to a recent assessment from the director general of the Russian think tank Strategia Vostok-Zapad, Dmitri Orlov, the organization is facing an unavoidable choice: to start developing an equal partnership immediately or continue the current practice of serving Chinese interests, which would be a dead end. If the first option cannot be effectuated, Orlov argues that Russia should pull out of the organization.

Still, it does seem that Russian leaders have in recent months been realizing the actual nature of the “friendship” with China. For instance, Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev gave an order to draw up a thorough list of goods that on strategic considerations should not be sold to China. Putin has recently called the government to apply protectionist measures against China, as Russia, a new member in the World Trade Organization, is threatened by the flood of light industry goods from China, which would come close to wiping out the corresponding sector in Russia. It is clear that that it is not the right development path for Russia to re-orient its trade from the European Union, which favours equal partnership, to a belligerent China in the throes of significant economic downturn and credit bubble – not if it wants to continue developing the major Nord Stream gas pipeline project with the EU and preserve its good existing cooperative relations with the European community.

Juhan Värk is a faculty member at the Estonian-American Business Academy, PhD in international relations and European studies